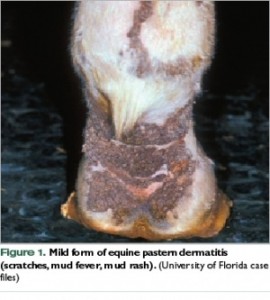

CHRONIC PASTERN DERMATITIS:

(Scratches, Mud Fever, Greasy Heel)

https://www.facebook.com/pages/PENZANCE-HORSEMANSHIP/116835991690990

Malandrinum :

http://www.homeovision.org/for-homeopaths/substances-und-homeopatic-remedies/malandrinum.html

Etymology

Family

Traditional name

English: Grease (Mud Fever)

Dutch: rasp, vorm van mok.

German: Der Pferdemauke

Used parts

* crusts from the grease heel. (6: used in the first prooving)

* Trituration of Sugar of Milk saturated with the virus. Solution of the virus. (1)

* exudate from the grease heel (5)

Classification

Keywords

Original proving

– The first proving: Dr. Boskowitz , Brooklyn (5,6)

– 1900 /1901: W.P. Wesselhoeft, H.C. Allen, Steere Holcombe and students from the Hering College. 30K 35K 200K. (5,6)

– Straube made provings of the 30th potency .(1,6)

Description of the substance

Grease is a chronic dermatitis in horses. Traditionally known as scratches, pastern dermatitis, grease heel or cracked heels.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION:

It first appears as small, well-demarcated, multiple ulcerations of the skin at the rear of the pastern in any one or all of the four legs. These ulcerations are covered with crusty exudative material and often bleed, especially during exercise and work. These small sores may seem to respond initially to treatment with topical medications but often reverse course, only to progress in severity and multiply in number. These multiple lesions often will coalesce into larger and more intractable areas of skin ulceration. They then become chronically infected, produce copious amounts of foul-smelling exudate and chronic thickening of the affected areas of skin.

Over time, these lesions spread up the leg, often affecting the skin as high as the knee and/or hock joints. These lesions are, at the very least, irritating and bothersome to the horses and, at times, can be quite painful. Severely affected individuals often exhibit generalized swelling in all four legs. In older, chronically affected horses, this enlargement of the lower limbs becomes permanent and is accompanied by thickened skin folds and the formation of large, well defined, hard nodules (called “grapes” by previous generations of horsemen). These nodules can become quite large, often “golf ball” or even “baseball” in size. The nodules themselves then become a mechanical problem because they interfere with free movement and are often injured or damaged during work.

CAUSE:

Horsemen and veterinarians have been arguing over the cause and possible treatments for this condition for decades. Everything from mange mites to bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus), fungi, trauma, moisture and chemical or plant irritants has been implicated as possible causes. Even the horse’s own hair, the luxuriant “feathers” that descend over the lower leg and pastern, have been blamed because it holds moisture and thereby provides the warm and wet environment on the skin surface which enhances the growth of fungi and bacteria.

In the late 1980s, a Dr. Tony Stannard of the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine made some preliminary microscopic analyses of the diseased areas of skin and classified what he saw as “Pastern Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis.”

Recently, scientists at the UC Davis Center for Equine Health have again taken up this work. These investigators have confirmed what Dr. Stannard suspected; that the degeneration of the vasculature has an immune-mediated component which is central to the production of disease. The research so far indicates that much of the damage caused to the skin and subcutaneous tissues of the lower leg and pastern may be a result of the horse’s own immune response to an inciting irritant.

In other words, the initial agent which attacks the skin is not important. A type of bacteria, fungus, or mange mites afflicts the horse’s skin which initiates a hyperactive or misdirected response by the horse’s own defense mechanisms. The animal’s own immune system then becomes the actual perpetuating cause of the problem. This “hyper” reaction by the body persists long after the original irritant (mite, bacteria, etc.) is gone which partially explains why the list of failed treatments is so long. Whatever particular treatment one employs, it may eliminate the particular pathogen present, but once that one is eliminated, another which is not susceptible to the medication chosen takes over because the horse’s skin is too busy fighting with itself to defend against any new invaders.

TREATMENT:

Cleanliness is extremely important to the long-term control and management of these lesions. The hair over the affected areas must be washed and dried carefully on a daily basis. This removes the dirt, debris and exudate that promotes and harbors the complicating microbes. While the clipping or removal of the feathers may facilitate the initial treatment of severely affected animals, it is not, in and of itself, a treatment for the condition; nor is hair clipping absolutely necessary for successful control of the problem.

It makes no sense to use highly toxic or irritating topical agents such as lead acetate paste or coal-tar type preparations.

One topical treatment that has shown, over time, to be useful in the control and management of the skin lesions is the daily application of sulfur based preparations. These come in two forms. The first is as a wetable sulfur dusting powder commonly used for disease control in plants.The second method of utilizing sulfur as a treatment is through the use of sulferated lime solutions.

Systemic corticosteriods are only effective when used in relatively high dosages. Therefore, they can only be used on a short-term basis in severely affected animals to assist in establishing a more stable basis for longer term therapy.

Additionally, mange mites definitely must be controlled as they can be both an inciting cause and a compounding stimulant to the condition. To control infestation on individual horses, a 0.25% fipronil solution (Frontline), the commonly used canine flea and tick control agent, can be used.

may I ask what homeopathic remedies you have found to be helpful? thanks

It’s been various remedies as layers have been worked on and relieved.

My mare, Star, has chronic crusty areas on all of her fetlocks. They are about the size of a thumbprint. Is this the same thing discussed here? They NEVER get as big as the picture,

and are mostly on the front of her fetlock /pasterns. Ideas? I think these have something to do with her immune system, would that bea correct assumption? She is 25 years old.

I do believe that UC Davis has the most comprehensive data available to the average horse person on this issue. It is one not to be taken lightly and if it perpetuates, it can easily become a chronic issue, IMHO.

Here’s a great article on it: http://www.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/ceh/docs/horsereport/pubs-HR19-4-bkm-sec.pdf

Homeopathy works on the body’s symptoms rather than the “disease” to get the body to return to its state of homeostasis so it can heal itself. That’s where the statement from the article states, “The initial agent which attacks the skin is not important.” is true adn why homeopathy can address the individual’s symptoms and keynotes. I use a combination, if necessary, of Homeopathy and Allopathic methods. 🙂 Not ‘classical’ in the homeopathic sense but intuitive, more or less, as to what may work. 🙂